- Anxiety can be a runaway train. The following six step thought management tool helps you slow it down and regain control.

- Step One: identify the raw worry thought. Just get it out there. It doesn’t matter if once you write it down it seems ridiculous.

- Example:

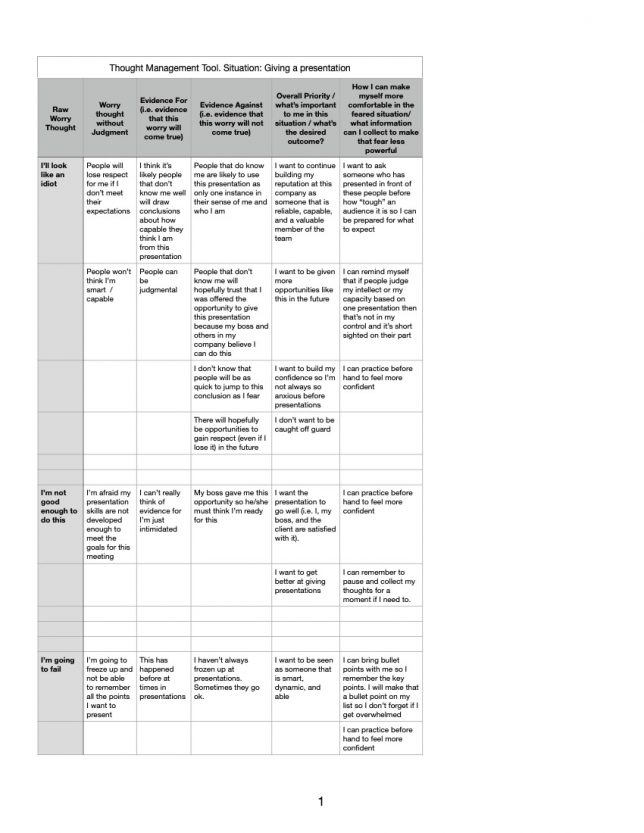

- I’m going to fail at giving this presentation

- Example:

- Step Two: Rephrase the worry thought so there is descriptive (rather than judgmental) language. This will enable you to get to the “core” of the worry.

- Example:

- “I’m going to fail at giving this presentation” BECOMES

- I’m going to freeze up and not be able to remember all the points I want to present

- People won’t think I’m smart / capable

- “I’m going to fail at giving this presentation” BECOMES

- Example:

- Step Three: List out all the reasons why you believe this worry could come true.

- Example:

- People can be judgmental

- people that don’t know me well may draw conclusions about how capable they think I am from this presentation

- I have frozen up during presentations before.

- Example:

- Step Four: List out all the reasons why you believe this worry won’t come true.

- Example:

- People that know me are likely to use this presentation as only one instance in their sense of me and who I am

- People that don’t know me will hopefully trust that I was assigned this presentation because others believe I can do this

- I don’t know that people will be as quick to jump to conclusions as I fear

- There will hopefully be opportunities to gain respect (even if I lose it) in the future

- I haven’t always frozen up at presentations. Sometimes they go ok.

- Example:

- Step Five: Now identify your priorities, goals, and what really matters to you about the situation you are in.

- Example:

- I want to build my reputation at this company as someone that is reliable, capable, and a valuable member of the team

- I want to be given more opportunities like this in the future

- I want to build my confidence so I’m not always so anxious before presentations

- I want the presentation to go well (i.e. I, my boss, and the client are satisfied with it).

- I want to get better at giving presentations

- Example:

- Step six: Identify what you can do to address the worries you hold (with respect to the priorities you’ve established), how you can troubleshoot for the things you know are likely to “go wrong”, and how you can help yourself feel more comfortable.

- Example:

- I want to ask someone who has presented in front of these people before how “tough” an audience it is so I can be prepared for what to expect

- I can remind myself that if people judge my intellect or my capacity based on one presentation then that’s not in my control and it’s short sighted on their part

- I can practice before hand to feel more confident

- I can remember to pause and collect my thoughts for a moment if I need to

- I can bring bullet points with me so I remember the key points and one of my bullet points can be the remember to pause and collect my thoughts when I need to

- Example:

One of the challenges with anxiety is that it can accelerate our thinking. We can get overwhelmed quickly – to a point where we can’t identify what we are thinking or feeling, we just feel anxious, out of control, and (often) helpless to stop it.

Therapists work to help their clients slow down the speed of anxious thoughts and come to understand them. The tool in today’s post helps you slow down worries, understand key concerns, reduce helplessness, and feel more in control (which is often one of the reasons anxiety gets so severe). This tool gets you focused back on what matters to you and what you CAN control.

I recommend starting with writing this down or typing it out. In time, this may become automatic enough that you can do it in your head.

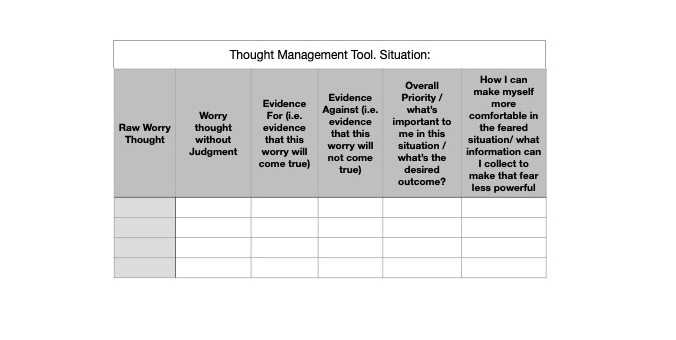

Step One. Raw Worry thought(s). You may have many, that’s ok, run through the exercise with each of them. The point of this column is to try and put words to the internal chaos so you know what you’re working with. Sometimes just clarifying the worry can help reduce anxiety.

Step Two. Rephrase the worry thought so there is descriptive (rather than judgmental) language. Judgments are often short-cuts that stop us in our tracks and leave us stuck in developing a plan of action. Substitute words like good, bad, right, wrong, should, shouldn’t, fail, succeed, hard, and easy with more descriptive language. See posts from 4/11-4/15 for detailed instructions on how to do this.

Steps three and four help challenge the likelihood of the worry coming true by forcing you to really think through the possibilities of what could happen.

Step Five: Pause and think through priorities. Look out for judgmental language here (i.e. instead of I want to do a “good” job, define what a “good” job means). The priorities for the situation don’t have to link up to the prior steps. This is a centering step to help you get to the heart of what matters to you and in this situation.

Step six: This gives you actionable steps, reduces helplessness, empowers you, and helps you gain control where control can be had.

After completing the exercise you are likely to feel centered and able to take steps to move towards meeting your goal(s)

Sample completed tool below for anxiety about giving a presentation:

Notes:

- Deconstructing judgments is a key step and one that may require more detailed instruction. If you’re getting stuck on this step read this post to help you identify a judgment, this post to learn more about how judgments limit us, and this post to learn more about how to deconstruct a judgment.

- I developed this tool, but it contains concepts merged from DBT and CBT